Present day photos taken by Suan Yong.

Back in the ‘80s, when I was studying computer science and historic preservation, I saw a recruiting poster for Digital Equipment Corporation. The poster, as I remember it, featured a young woman programming a PDP-11 at DEC headquarters.

That was The Mill, an adaptive re-use of a 19th century woolen mill in Maynard, MA. I wanted to be like her. Eventually, I did work at a former DEC headquarters building in Maynard, but not at The Mill and not for DEC. Driving past the old brick walls on the way to work, I remained wistful.

Enter GrammaTech

When I joined GrammaTech in 2009, the company was located in a Queen Anne residence/carriage-house combo it had already outgrown. At that time, economic development was in full swing in another part of Ithaca: the industrial West End. Earlier initiatives in that part of town had eliminated an infamous intersection known as The Octopus. The latest development activity meant even more to me personally―a great gym and a better boat yard.

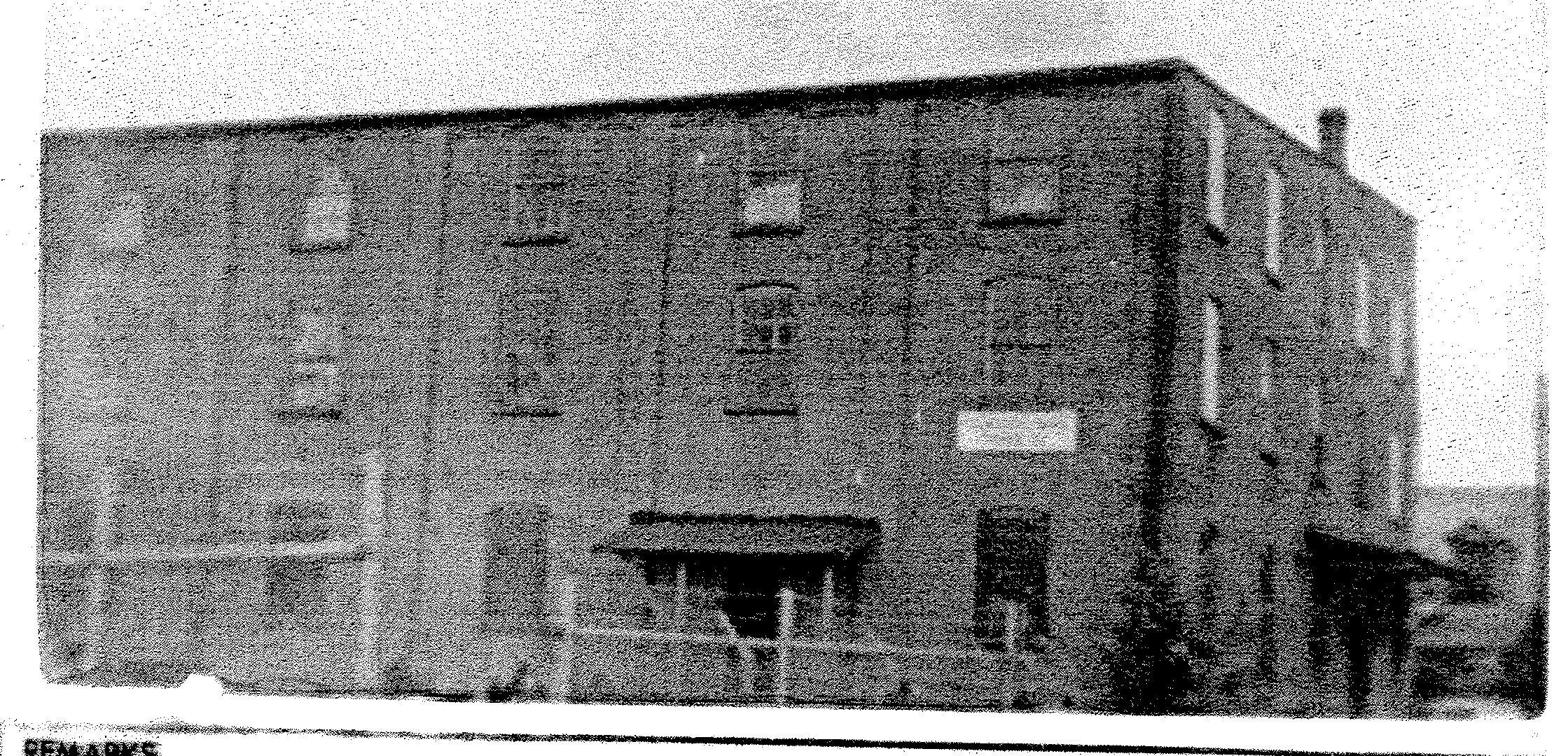

There were also plans for a restaurant at the warehouse by Fulton and Esty Streets. I’d hardly noticed that building until two things happened. First, Fulton became the primary route to town from my house. Second, the development firm ARCHE, LLC and the architectural firm Holt grabbed my attention by inserting a three-story glass atrium into the Esty St. facade and making the fenestration pop with metallic green paint.

I wish what happened next had been my idea, but it wasn’t. The developer and our CEO ran into each other on the Cornell Campus-to-Campus bus from Ithaca to NYC, and started talking. The restaurant deal hadn’t materialized, and GrammaTech needed more room. The building was almost at move-in condition, but not quite. For example, even 1.5 inches of oak wasn’t thick enough to function as our server room floor. And sixteen massive posts supporting each floor made office layouts tricky. But after modest adjustments, Ithaca’s West End welcomed us in 2010.

T.G. Miller and the Lehigh Valley Railroad

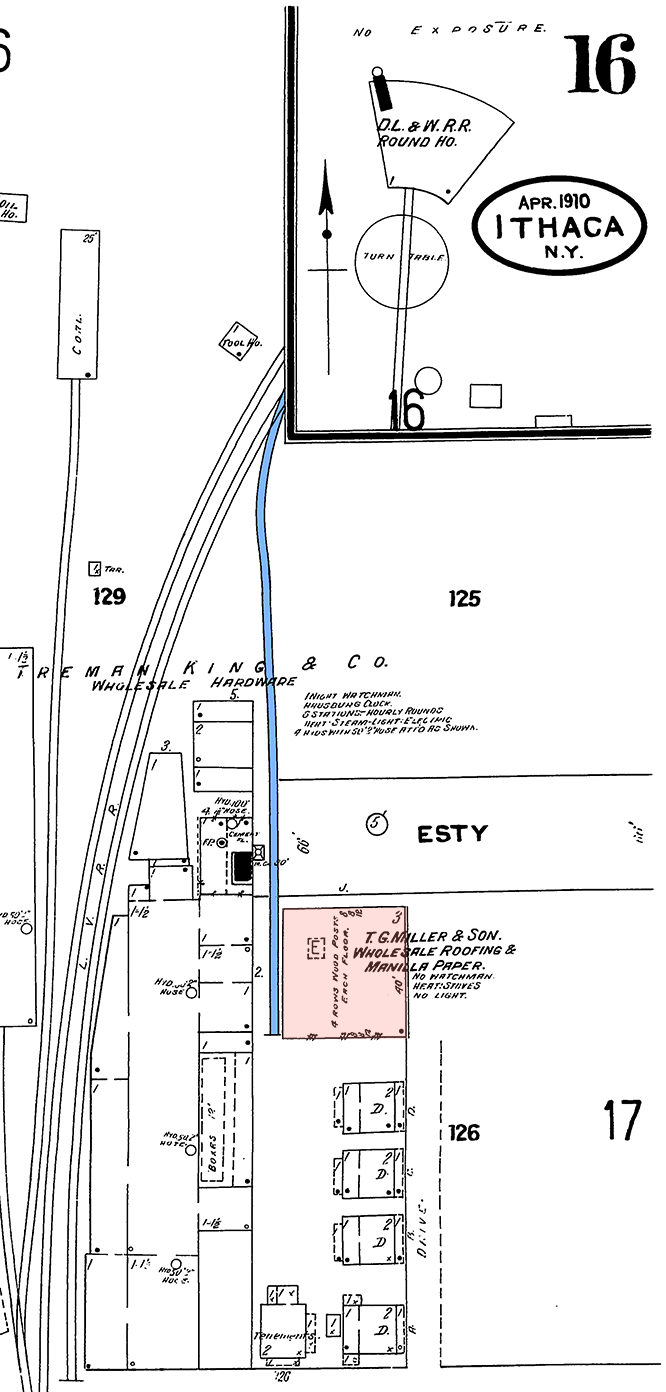

A hundred years before our move, the building first appeared on a map created by the Sanborn Company for insurance purposes. Our property is labeled T. G. Miller & Son, Wholesale Roofing and Manilla Paper (shaded in red). Knowing something about where I work, my brother Tom likes to ask how things are going at the paper mill. I correct him. It was a warehouse―not a mill. But he really isn’t that far off.

Thomas G. Miller manufactured paper nearby, at the foot of Ithaca Falls, with his partner Frank J. Enz. In 1886, they had purchased the water-powered mill from their former employer, Andrus, McChain & Co., hired twenty people, and started turning out 3-4 tons of brown paper a day. Their first stationery store opened at 20 N. Aurora St. Boomers remember the penultimate store at 328 East State St. not only for the paper―vertical shelves of cut-to-measure sheets in so many colors and weights―but also for the sign―a huge pencil alongside the vertical drop of the MILLER name. A favorite possession of mine is a 1,000-count box of manila string tags, now down by half. I like to think my box sat in the warehouse a year or two until they ran out at the store.

The warehouse isn’t the only relevant feature on that 1910 Sanborn map. The other feature is a railroad siding shown along the west side of the building (shaded in light blue). Freight trains still go through here, running up the lake with coal and returning with salt. You can feel it in our building when they pass.

There used to be a passenger train, too. The Black Diamond carried Ithacans to NYC and to Buffalo. The railroad siding was the result of an agreement between T. G. Miller and the Auburn Division of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. The railroad company agreed to build and maintain the siding; the paper company agreed to use the railroad, and only the railroad, for incoming shipments.

Railroad cars fully loaded with paper would be pushed and decoupled at the double doors, giving warehouse workers time to unload. Since the first floor is well above ground-level, cartons could sometimes be rolled directly into the building; if not, ramps were used, slanting up or down depending on the height of the boxcar. Just inside towards the left, a freight elevator waited for someone to pull the cable and start the ascent.

Entrances and Exits

Our address is 531 Esty St. I confused the name with the handmade goods site until I started this blog. Then I learned that Joseph Esty was a director of the Ithaca Gaslight Company. He built worker housing on what was called New St. until they renamed it after him. In the pre-Miller Sanborn map of 1904, the building on our site holds offices for the sprawling Ithaca Wall Paper Mills.

The Miller warehouse, even at the start, supplied more than the company store. Horse-drawn vans and soon trucks were loaded at what is our main Esty St. entrance on the north side. They delivered supplies to schools, mom-and-pop stores, and other stationers throughout the Southern Tier, including Northern PA and Central NY towns like Moravia, Groton and Dryden. The least imposing entrance to the building, not counting the half-height basement door on the south side, was from what now is an alley on the east side called Allen St. The 1921 City Directory lists 116 Allen as the T. G. Miller address; in 1925 it was listed as 118-120 Allen. Trucks backed into Allen St. for a three-point-turn. Warehouse staff climbed stairs to a porch and walked into the building through the now-defunct Allen St. door.

One day, the pedestrian at the Allen St. entrance was John Reps, an historian who also happened to be my thesis advisor as well as our President’s dad. When Prof. Reps couldn’t find what he needed at the stationery shop, they took him to the warehouse. He waited in a gloomy vestibule, lit only by bare 40-watt bulbs dangling from single wires above his head. None too soon, the needed supplies were found, probably index cards for his humongous library-style catalog.

The warehouse remained a warehouse until 1999. During that time, the only non-Millers to own the company and the building were the last owners. When William and Dorothy Benedict took over in 1983, they weren’t exactly strangers to the business. Bill started working there as a high school student in 1952. He was a go-fer, sweeping floors and running mail, until he graduated and went full-time―first as employee, then boss. As far as I can tell, he knows the exact size and location of all the paper stored in the building during his tenure, the second half of the Twentieth Century. Maybe he even wrote the inventory record of “colored Drag” that’s still visible on a structural column outside our Executive Office suite.

Eventually paper bags lost the contest with plastic and the practice of maintaining large inventories was replaced with a system of ordering stock on demand. The Benedicts sold the warehouse to ARCHE, LLC for its second act.

Inside the Warehouse

Today, most Ithacans know the warehouse as “the place on your right” when you’re waiting to get into our popular Friends of the Library Book Sale. But Benedict knows the details. Utilitarian papers were kept on the first floor―cartons of bags, toilet paper, paper towels, and meat wrap―while reams of writing and printing papers―mimeo, printer, copier and bond (8.5 x 11, 17 x 22 and 28 x 34)―were kept on the third floor. The higher floor might have prevented the warping problems that Willis Carrier, a Cornell grad, had solved for a publisher by inventing air-conditioning. The ceiling on the highest floor is sloped and somewhat challenging for tall people who visit the low side. This bug/feature facilitates water run-off and provides an up-close view of the iron hardware and massive wooden posts and beams that remain fully exposed throughout the building.

The second floor held offices and bathrooms. The offices were heated. The bathrooms, like the other floors, were not, though they got some warmth from the furnace below. Now, we have both heat and Mr. Carrier’s air-conditioning.

In 1910, the building lacked electricity. The need for natural light inspired the architecture, which mimics the equally dark commercial buildings of the Industrial Revolution. Six-over-six double-hung sash windows puncture the brick walls and really make the building. On every side of the freestanding structure, fifteen windows are arranged in five bays on three floors. Red brick forms an arch above every window and the arrangement of the bricks is unusual― five courses of stretchers and one of headers. Stu Lewis, a retailer-turned-realtor who showed the building in the 90’s, remembers how buildings like this used to be “kicked around like an unwanted relative.” Now, as never before, industrial is chic.

Up on the Roof

Our building is at lake-level, and hills rise all around us. Even on the roof, you feel like you’re in a wavy, tree-lined bowl. Here, the historical context of the building is plain as day. Just past the train tracks, you see their partner and predecessor, the Old Cayuga Inlet. Hard as it is to imagine now, the inlet was a busy commercial waterway when the Erie Canal was completed in 1825. A small island separates it from the main inlet to Cayuga Lake. The main inlet was dredged and straightened in the late 60’s by the US Army Corps of Engineers as a flood control channel and―something extra. It accommodates a three-lane 2,000 meter Olympic rowing course, symbolizing the transition of the West End from commercial to recreational use.

From the roof, whether you turn north or south, you see a food landmark―the red and white awnings of Purity Ice Cream (est. 1938) and the umbrellas shading picnic tables at Ithaca Bakery (est. 1910). Looking up East Hill, the sometimes intimidating Cornell campus stretches from the Arts Quad to the Engineering Quad, never seeming to exceed the width of the roof.

Fact Meets Fiction

Life in our paper warehouse isn’t without its Dunder Mifflin moments. Sometimes we squabble over parking spaces and the right way to do almost anything. You might find us desperately seeking cell phone privacy in a vestigial corner or the loading dock. We play silly games at picnics. And, as Ed Catmull once said about his management style at Pixar: we’re allowed to inter-marry. Fortunately, our CEO is more Catmull than Scott. And the rest of us? More Pam and Jim than Angela and Dwight. Long may we run.